Choosing real people from history to spin into a tale of fiction is one of the most interesting parts of planning a new story. Throughout The Marquess House TrilogyI’ve tried to tell the tale through the voices of women. These incredible ladies lived over 500 years ago and there was a huge number who were clamouring to have

their stories told.

As well as my more well-known main characters, I’ve tried to include the women who have been pushed to one side of history. Their stories are equally as fascinating as the queens, the princesses, the duchesses and the countesses; and their actions often impacted on social and political events, even though their input may have been forgotten by subsequent generations.

One of my favourite discoveries for the second part of the trilogy The Elizabeth Tudor Conspiracywas Lady Katherine Paston. Born around 1547, Katherine provided me with a female blood link between Catherine Howard and Elizabeth I. It came through the Culpeper and Leigh line, which was from Catherine Howard’s mother, Jocasta Culpeper.

However, upon further digging, I also discovered that Katherine Newton was linked to Elizabeth I through a connection to the Boleyn family; the paternal line of Elizabeth’s mother, Anne Boleyn.

Katherine’s mother was Agnes Leigh, the daughter of Catherine Howard’s troublesome half-brother, John Leigh and, his wife, Elizabeth Darcy. When she was queen, Catherine Howard, begged her husband, Henry VIII, for clemency for John Leigh, securing his release from prison. John and Elizabeth rather unusually divorced sometime before he made his will in 1563.

There is no information concerning Agnes’s birth, although by 1544 she had married Sir Thomas Paston. He was a gentleman of the privy chamber and part of the powerful Paston family from Norfolk. Agnes and Thomas had three children: Henry (b. 1545), Katherine (c. 1547 – 1605) and Edward (1550 – 24 March 1630).

As well as his position in the privy chamber, Katherine’s father, Sir Thomas Paston, was also an MP for Norfolk. He was respectable, powerful and well-connected. His father, William Paston had married Bridget Heydon, the daughter of Henry Heydon and Anne Boleyn (senior) who was the paternal aunt of the future Queen Anne Boleyn. The Pastons and the Boleyns were both wealthy and influential families.

Katherine’s father died on 4 September 1550. After this, Agnes married Edward Fitzgerald MP, giving young Katherine a host of half-siblings, including included Douglas Aungier (a sister); Thomas Fitzgerald; Lettice Fitzgerald and Gerald Fitzgerald, 14th Earl of Kildare. There was certainly no doubting Katherine’s connections, yet, she is practically unknown.

In The Elizabeth Tudor Conspiracy, I used Katherine’s connections to the Paston family, who were voracious letter writers, to place her at the heart of Elizabeth’s network of informers, the Ladies of Melusine. Whether she was even literate is not clear but I would guess she was, especially considering her family background. One of the contemporary comments made about Katherine was that she was supposed to suffer from ill health, which caused her absence from court. While I haven’t been able to verify this, I liked the idea and used her ‘illnesses’ as a cover for her being able to disappear for days at a time in order to write letters on behalf of Elizabeth and to deal with the correspondence of the Ladies of Melusine.

Finding Katherine’s voice, however, has proved difficult and despite extensive searching, I have been unable to discover any surviving documents written by her. As a married woman, she would not have made a will and there seem to be no letters. There is another Katherine Paston whose words have been preserved but these are not written by the correct Katherine.

The first mention of our Katherine, is in Henry Clifford’s book, The Life of Jane Dormer, Duchess of Feria, suggesting that in 1559, Katherine was in Spain.

Jane Dormer had been a lady-in-waiting for Mary I but on her death in 1558 and Elizabeth’s ascension to the throne, Jane had married Gómez Suárez de Figueroa y Córdoba, 1st Duke of Feria. Both staunch Catholics, they returned to Spain. Clifford suggests that Katherine was the Mistress Paston who was named as being part of the duchess’s household. This would have made her 12-years-old but it is possible. Despite being Catholic, Jane Feria was said to have kept in touch with the Protestant, Queen Elizabeth, whom she had known since childhood.

After this, events become a little blurred. I have found two possible dates for the marriage of Katherine Paston and Sir Henry Newton (1535 – 2 May 1599). One is 1560, which would make Katherine 13 years old, while the other is May 1578, making her 31. As women married young, my guess would be the earlier date, particularly as her children’s births run from c. 1570 to 1584, suggesting she was 23 when she gave birth to her first child. It is likely the marriage was in name-only until Katherine reached maturity.

The confusion comes from a fragment of a court record dated 15 February 1577, which seems to suggest Katherine Paston might marry Lord Stourton. From the dates, this was probably John Stourton, 9th Baron Stourton (1553 – 1588). He was the son of Charles Stourton, 8th Baron Stourton who had been executed for committing the crime of murder on 16 March 1557. However, other records show she was already married to Sir Henry Newton by then and had several children. Lord Stourton instead married Frances Brooke. A list of marriages below this fragment place the date ‘1578’ beside Katherine. I wonder if this was perhaps the day she returned to court after an absence rather than as the indication of her marriage. (https://folgerpedia.folger.edu/The_Elizabethan_Court_Day_by_Day)

Katherine’s husband, Henry Newton, was the eldest son of Sir John Newton of East Harptree and his first wife, Margaret Poyntz. He would have been 25 when the marriage to Katherine took place. This was not uncommon and perhaps this is why Katherine is listed as being in Spain. She may have been sent there in order to complete her education, returning when she was old enough to enter the marriage.

It is probable that Katherine and Henry lived at Barr’s Court in East Harptree, Somerset which was the family seat of the Newton family. Nothing of the house remains but there are records that the ancient mansion once looked out over Kingswood Chase, a royal hunting forest, on the outskirts of Longwell Green. The mansion is discussed by the historian John Leland in 1540 when he describes it as a ‘fayre old mannar place of stone’. There are also records suggesting the property boasted a moat, more for decoration than defence, two fishponds, a dam and a vast parkland.

The couple had six children: Frances, Margaret, Theodore, John, Anne and Elizabeth; suggesting their marriage was functional and happy. Although there are very few remaining records concerning family life, perhaps the suggestion that Katherine was often ill, might have been due to her pregnancies.

Katherine is first listed as being a lady-in-waiting to Queen Elizabeth I in 1576. A sought-after position with status attached. It is well-known that Elizabeth favoured her mother’s family, the Boleyns. The offspring of Mary Boleyn were prevalent at her court and were given the not altogether flattering nickname of The Tribe of Dan, a Biblical reference to one of the powerful tribes of Israel. Katherine, with her direct bloodline to Queen Catherine Howard, who had been first cousin to Elizabeth’s mother, Anne Boleyn, and a paternal link to the Boleyn family, was definitely part of the family and by 1598, Katherine was one of the senior ladies of the court.

Family life would have run alongside court life and as Katherine and Henry’s brood grew, they would have divided their time between Henry’s estates in Somerset and Gloucester and the glittering life of court. However, it is possible tragedy struck. In Henry’s will, his youngest son, Theodore, is listed as his heir, stating the child was 15-years-old when his father died in 1599, giving him a birth date 1584. This is a sizeable gap between him and his siblings whose births were in the 1570s. The inscription on Henry’s tomb declares he was the father of two sons and four daughters. There is also an interesting comment made about Katherine after Henry’s death. It states that not only did Katherine oversee the creation of an impressive tomb for her husband in Bristol Cathedral but that she also raised a monument to her father-in-law, John Newton in the church at East Harptree in Somerset.

While this is possible, I suspect the true person to whom this tomb was dedicated was Katherine and Henry’s son who bore the same name. Young John vanishes from the records suggesting he died as a young man. As East Harptree was the family church, it would make sense that they would bury their son there. Katherine and Henry may then have decided to try and have another child, a new heir. Another possible reason why the real Katherine was absent from court with illness. Miscarriages, sickness or other symptoms could have kept her from her duties. Theodore was born in 1584, when Katherine would have been 37. He was probably her last child and pregnancy.

As with all large families, there were plenty of squabbles and Katherine’s marriage embroiled her in a family feud. After the death of Henry’s father, Sir John Newton, in 1568, a row erupted between Henry, his stepmother, Lady Jane Newton, and her son, Thomas Buckland. Lady Jane had been left a life interest in the manor of Netherbadgworth, Somerset, but she claimed the right to make arrangements about tenancies of the property. Henry refused to recognise these conveyances and a Chancery case resulted.

By 1580, they were at such loggerheads the case was taken to the Star Chamber, Chancery and the common law courts, who all tried to settle the family disputes. By then, the focus had shifted to Thomas Buckland’s claims to dig for iron ore in the Mendips at East Harptree and elsewhere. Henry Newton was furious and claimed that Buckland and his accomplices had not only illegally carried off lead ore worth £400 but had caused serious disturbances of the peace by their violence. Unfortunately, the outcome of the case has been lost.

Land disputes aside, it seems Henry was still an important man at court and Queen Elizabeth expressed a fondness for Katherine’s husband, showing him favour by bestowing a coveted and lucrative wardship upon him. She also sent him a note expressing her condolences when his son-in-law, Giles Strangeways died in 1596. He had been married to Katherine and Henry’s daughter, Frances, and Henry must have had a close relationship with Giles.

Henry was so overwhelmed by Elizabeth’s thoughtful gesture, he wrote to Robert Cecil stating that he would keep the queen’s ‘most gracious comfort sent me down by you’ as the most ‘precious thing which I shall ever had, and so leave it to my son’. Daily in his prayers he asked God to ‘increase those most excellent and royal graces in her which never any historians have recorded in any Queen as in our most excellent paragon’.

Despite this, Elizabeth could still be contrary and in January 1598 when Katherine requested the position of maid of honour for one of her daughters, she was unsuccessful in her request and Elizabeth Southwell was appointed instead. Although, as Mistress Southwell was the granddaughter of Catherine Carey and the great-granddaughter of Mary Boleyn, Elizabeth’s maternal aunt, her selection becomes more understandable and less of a snub towards Katherine and her daughters.

When Henry died on 2 May 1599 at East Harptree, he left a lengthy will with many Latin quotations. He was obvious a loving and caring father, as he created healthy dowries for his daughters and instructed Katherine’s brother, Edward Paston, to be executor. Although I have not yet found details of Katherine’s inheritance, if Henry was generous to his daughters and other members of the family, it is probable Katherine was left with a substantial dower and a comfortable lifestyle.

After Henry’s death, Katherine and Henry’s eldest son, Sir Theodore Newton inherited his father’s estate. Theodore married Penelope Rodney and it was their son, Sir John Newton who would rise to the aristocracy when he was made 1st Baronet of Barr’s Court. This title was bestowed upon him by Charles II on 16 August 1660 as thanks for providing troops to defend the plantation of Ulster. However, as John had no heir, when he died, it passed out of the Gloucestershire Newton family to the Lincolnshire Newtons. Strangely, there was no blood link between them.

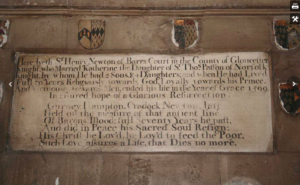

The widow, Katherine, continued to express her love and loyalty to her husband, with the creation of a large dresser tomb built to Henry at Bristol Cathedral, where several years later, she too was interred. The tomb survives to this day and is in the Newton Chapel at Bristol Cathedral between the Chapter House and the south choir aisle. It is elaborate and elegant, demonstrating their elevated status and their blood links to many important families. Below the recumbent effigy of a serene and bearded Henry, their children are shown kneeling, with their hands in prayer, facing the scriptures to represent piety and obedience.

The inscription reads:

“Here lyeth Sir Henry Newton of Barr’s Court in the county of Gloucester, knight, who married Katherine the daughter of Thomas Paston of Norfolk, knight, by whom he had two sons and four daughters and when he had lived full 70 years religiously towards his prince, and virtuous towards men, ended his life in the year of grace 1599 in assured hope of a glorious resurrection.

Gurney, Hampton, Cradock, Newton last held on the measure of that ancient line of Barons Blood, full seventy years he past and did in peace his sacred soul resign: his Christ he lov’d, he lov’d to feed the poor sure love assures a life that dies no more.â€

Katherine’s date of death is recorded as 1605, two years after Elizabeth I’s demise. In 1603, Elizabeth was replaced on the throne by James I, the son of Mary, Queen of Scots. The new king’s court swept away the old hierarchy and Katherine, a widow of 56, would have been dismissed along with Elizabeth’s other women, with only a few bright stars from the Tudor court remaining at the heart of events.

Lady Katherine Paston was born into the privileged classes of Tudor England, that period of great change in British history. She was connected by blood to two queen consorts of Henry VIII and she married a respected and successful man. Five of her six children survived into adulthood and through her son, the family was raised to the levels of Baronet.

During her life she witnessed four Tudor monarchs, three of whom were queens: Edward VI, Lady Jane Grey, Mary Tudor and Elizabeth. Each reign, no matter how brief, making its mark on history. As a lady-in-waiting to Queen Elizabeth, Katherine was at the beating heart of the Tudor court. She witnessed the subterfuge, the brilliance, the rise of the arts, the skulduggery, the terror of threatened wars, the power of a queen when she had to fight to save her country from the Spanish Armada.

Katherine was there. She witnessed these events and while she may have been pushed into the shadows of history for centuries, this brief glimpse of her life, proves that no matter who you are, where you were born or when you lived, hers was a life lived and this is my tribute to her.

Lady Katherine Paston Newton

(1547 – 1605)

References:

https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1558-1603/member/newton-henry-1531-99

https://folgerpedia.folger.edu/mediawiki/media/images_pedia_folgerpedia_mw/3/3c/ECDbD_1577.pdf

http://www.tudorwomen.com/?page_id=701

https://www.geni.com/people/Sir-John-Newton-of-East-Harptree/6000000000806387332

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Leland_(antiquary)

https://www.flickr.com/photos/brizzlebornandbred/3240276893

Family tree fragment:Â https://gw.geneanet.org/frebault?lang=en&pz=henri&nz=frebault&p=catherine&n=paston

https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/cross_fac/iatl/reinvention/archive/volume8issue2/barnett/

https://barrscourtmoat.wordpress.com/author/lisjardine/page/3/